Positive Risk Coaching Framework

Enhancing mountain bike instruction using risk as a tool for development

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- How to Use This Framework (Read This First)

- What We Mean by “Positive Risk”

- The Four Domains of Risk (Diagnostic Lens)

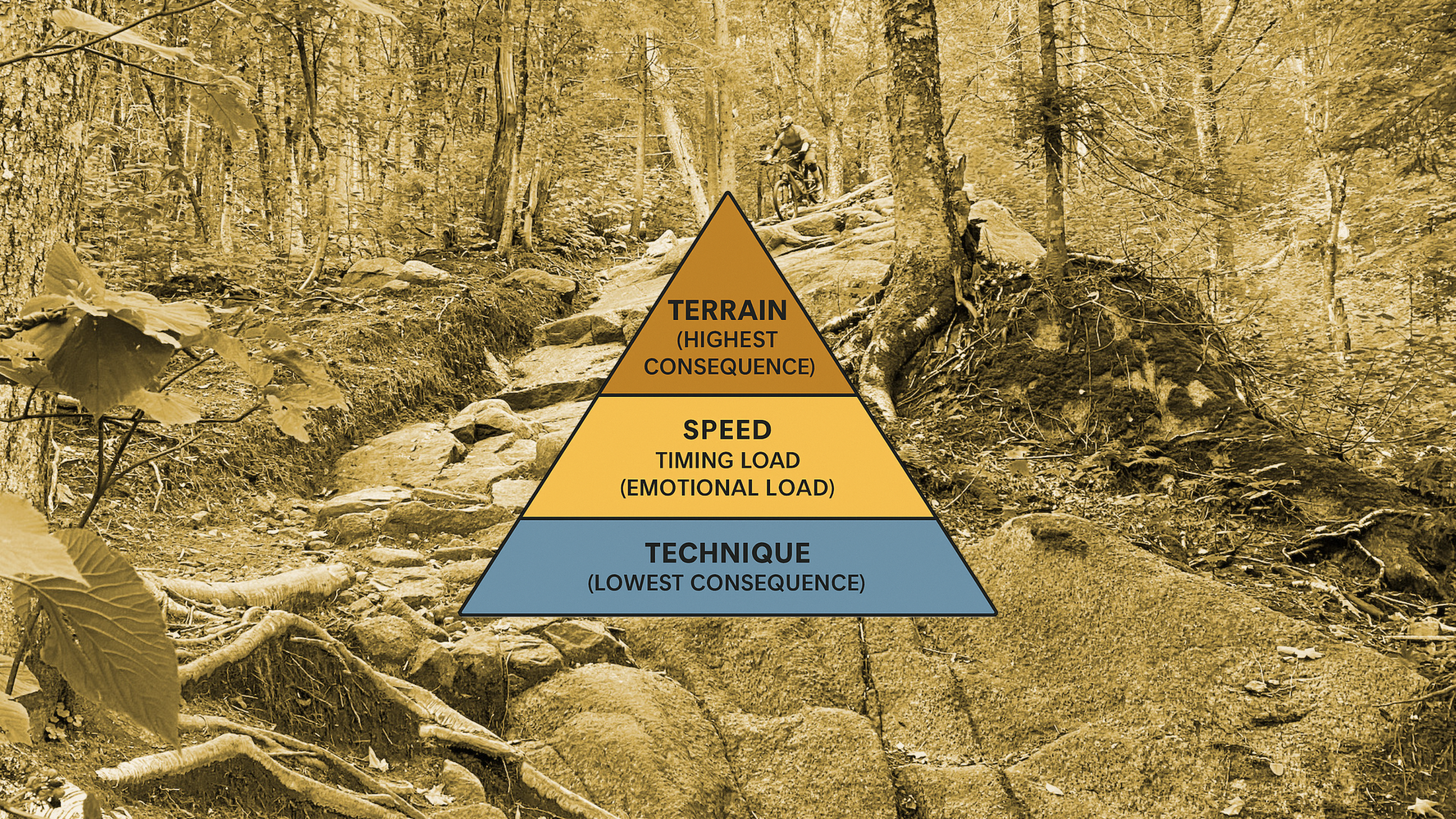

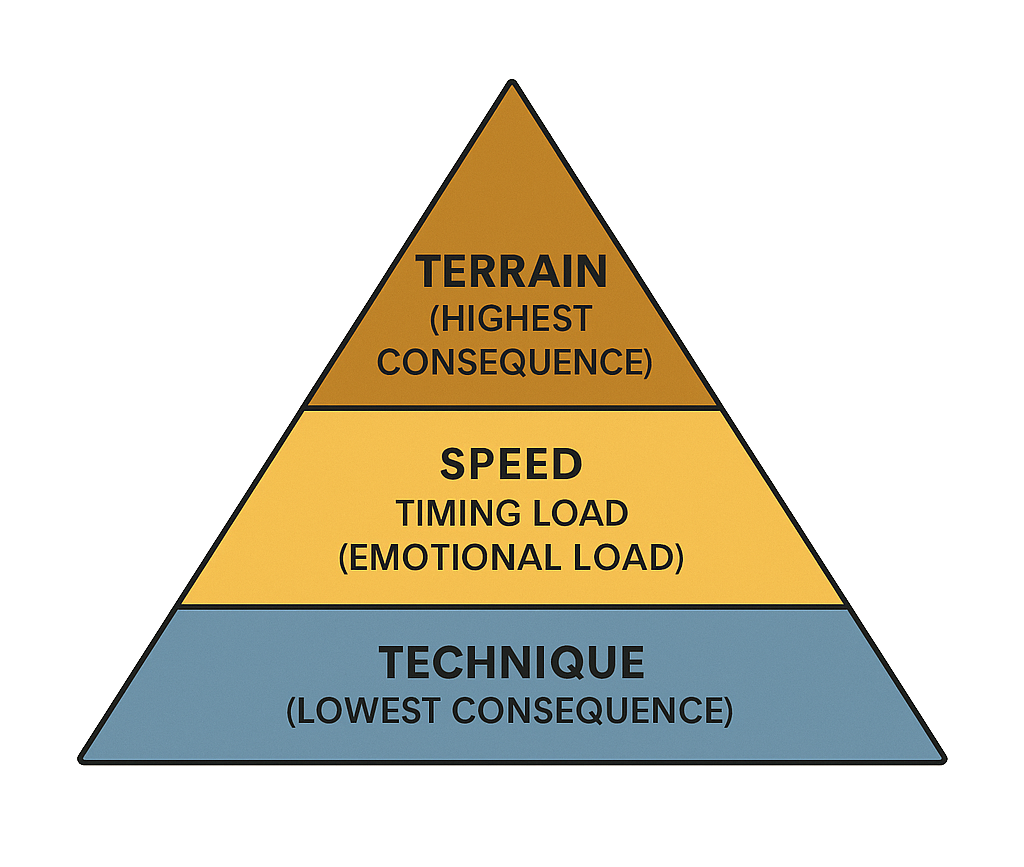

- The Positive Risk Triangle (Sequencing Tool)

- The Positive Risk Progression Loop (Operational Model)

- Coaching Behaviours That Enable Positive Risk

- Outcomes: What This Produces Over Time

- Summary: What Positive Risk Actually Does

Introduction

Risk is an unavoidable part of mountain biking. Every time riders enter unfamiliar terrain, increase speed, or attempt new skills, they engage with uncertainty and consequence. For instructors, managing this risk is not optional—it is central to effective teaching.

Professional coaches already manage risk explicitly or intuitively through experience, judgment, and professional training. However, intuition alone can lead to inconsistency. Similar riders may be progressed differently, challenges may be introduced too early or too late, and setbacks are sometimes misattributed to a lack of skill rather than to excessive or poorly managed risk.

This framework is written for instructors at all levels, particularly those with some teaching experience, who want to improve the quality and consistency of their coaching.

The Positive Risk model helps clarify how challenge, skill development, and rider readiness interact within lessons, lesson planning, and longer-term programming. It does not replace existing curricula or instructional methods. Rather, it provides a structured way to name and organize influences instructors already manage—often intuitively—so they can make more deliberate and informed coaching decisions over time.

How to Use This Framework (Read This First)

This framework is intended as a practical decision-making tool. Instructors do not need to apply every element rigidly or in sequence. Instead, it should be used as a lens for lesson design, terrain choice, and moment-to-moment coaching decisions.

In practice, the model can be used:

- During lesson planning, to anticipate how and where risk may increase

- When delivering lessons, to decide whether to adjust speed, terrain, or task complexity

- If riders hesitate, stall, or regress unexpectedly

- As needed to balance progression, confidence, and safety

The sections that follow build toward application:

- The Four Domains of Risk support error detection and diagnosis beyond technique alone

- The Positive Risk Triangle helps sequence challenge

- The Progression Loop structures how risk and skill are introduced and applied

- Coaching Behaviours and Outcomes reinforce how instructor actions influence learning

The framework is iterative, not linear. Instructors should expect to move forward and backward through it as rider readiness, conditions, and goals change.

What We Mean by “Positive Risk”

Risk is already addressed across mountain bike instructor curricula, including PMBIA, BICP, and GSMBC. In these frameworks, risk refers to the presence of uncertainty and potential consequence inherent in providing sport instruction.

Risk management is the professional responsibility to reduce unnecessary exposure and avoidable consequences through planning, terrain selection, communication, and supervision.

Positive risk is the intentional use of manageable uncertainty to support learning and development. In coaching contexts, positive risk exists when riders are exposed to challenge that is appropriate for their technical ability, emotional readiness, and the environment in which they are riding.

Positive risk is not about pushing limits indiscriminately, but about shaping challenge explicitly and intentionally, so that it contributes to skill acquisition, confidence, and improved lessons.

The Four Domains of Risk (Diagnostic Lens)

Instructors already analyze performance through lesson plans, drills, demonstrations, and error detection and feedback. The Four Domains of Risk are intended to augment this existing analysis by making risk more functional within instructional decisions.

Working within existing approaches to skills instruction, coaches can ask where risk may be present, accumulating, and influencing rider performance.

A. Technical Risk — What the Rider Is Asked to Do

Technical risk relates to the physical demands, movement, coordination, and timing required to complete a task.

In lessons, technical risk is shaped by:

- Drill selection

- Skill breakdowns

- Task complexity and constraints

- Progression of movement patterns

B. Environmental Risk — Where the Skill Happens

Environmental risk reflects the terrain and conditions in which a skill is performed.

This includes:

- Terrain choice, slope, obstacles, and surface conditions

- Exposure and perceived consequences of mistakes

- Visibility, weather, and trail traffic

Environmental risk is largely controlled by instructors through trail selection and feature choice and can dramatically amplify technical and psychological demands, even when the skill itself is unchanged.

C. Psychological Risk — How the Rider Feels

Psychological risk describes a rider’s emotional and cognitive response to challenge. Fear, anxiety, excitement, or pressure can reduce a rider’s ability to process information, regulate movement, and apply technique consistently.

In lessons, psychological risk is often influenced by:

- Perceived complexity of the task or terrain

- Novelty or unfamiliarity of the skill or environment

- Time pressure or expectations to perform

- Previous experiences, successes, or failures

- How challenge is introduced, framed, and progressed

Instructors often detect elevated psychological risk through hesitation, rigidity, avoidance, or over-arousal. Making this domain explicit allows instructors to adjust challenge before performance breaks down, rather than attributing issues solely to technical ability.

D. Social & Professional Risk — The Coaching Environment

Social and professional factors shape how safe riders feel engaging with challenge. These factors influence trust, willingness to attempt tasks, and how riders interpret feedback. In most lesson scenarios social factors should be actively monitored and managed by instructors.

These include:

- Lesson formats and products with appropriate student numbers

- Instructor communication and teaching style

- Clarity of lesson structure and boundaries

- Group dynamics and comparison pressure

- Perceived expectations and judgment

Even in low-consequence terrain, poorly managed social risk can undermine learning.

The Positive Risk Triangle (Sequencing Tool)

The Positive Risk Triangle provides a conceptual model for sequencing challenge within and across lessons. Its purpose is not to prescribe drills or teaching methods, but to help instructors decide what variable to adjust next when progressing riders.

The triangle is structured around three common primary layers: technique, speed, and terrain. These layers represent increasing consequence and commitment, and should generally be addressed in that order.

A. Technique — The Foundation

Technique forms the base of the triangle and carries the lowest consequence. In skills based teaching, this is core competency and instruction delivery. Skill acquisition and refinement are most effective when riders can focus on fundamental skill components like body position, braking, pressure control, and timing without the added complexity of speed or terrain. This layer drives skill acquisiton through targeted movement and patterns, predictable environments, and high repetition with low consequence.

Errors at this level are expected and manageable, making technique the safest and most effective starting point for any lesson or skills progression at any rider skill level.

B. Speed — Timing Load Without Terrain Consequence

Speed increases risk by compressing the skill execution window, requiring timing and power refinement, and reducing margins for error. It exposes weaknesses in movement patterns and timing while remaining more controllable than terrain-based progression with less potential consequence.

Speed is often the most effective progression lever because it allows instructors to increase challenge while maintaining environmental control. Many riders benefit more from improved timing and consistency at moderate speeds than from immediately attempting more difficult terrain at prescribed speeds. Execution at both faster and slower speeds adds challenge and drives improvements necessary for riders to adapt to obstacles and terrain.

C. Terrain — Validation and Commitment

Terrain introduces real-world complexity, commitment, and consequence. It naturally adds visual information and complexity to drive trail awareness and scanning skills, provides multiple line choices, and introduces exposure elements that are not fully replicated in controlled environments.

Terrain should be used to validate preparation and refine execution, not necessarily to create it. Riders should attempt more difficult obstalces and enter higher-consequence terrain only after demonstrating Consistency, Control, and Confidence (CCC) through technique and speed progression.

Confidence as a Governing Principle

Confidence governs movement through the triangle, but it should never be used as a substitute for preparation and validation. A rider’s belief that they are ready does not replace being Comfortable, Consistent, and Correct (CCC) in technique, execution across different speeds, or correct application on incremental terrain.

Outward confidence alone is not a reliable indicator of readiness. A rider may feel prepared to attempt a high-consequence feature immediately after initial skill practice, but effective progression requires validating confidence through appropriately scaled terrain that builds commitment and risk gradually. Skipping intermediate steps typically reduces skill consolidation and increases the likelihood of confidence breakdown rather than development.

Instead, confidence functions as a feedback loop between preparation and exposure. Effective coaching uses psychological support, managed challenge, and clear opt-out to protect confidence while validating readiness.

Triangle Principles

- Do not skip layers. Moving directly from technique to terrain is a common cause of fear spikes and performance breakdown.

- Spend more time at the base than intuition suggests. Most riders need better mechanics at moderate speed, not harder features.

- Use speed before terrain to increase challenge while maintaining control.

- Treat terrain as validation, not acquisition. It confirms preparation rather than creating it.

- Progress only when riders demonstrate Consistency, Control, and Confidence (CCC).

The Positive Risk Progression Loop (Operational Model)

The progression loop provides a structured, repeatable method for guiding riders through skill development while explicitly managing all four domains of risk. It aligns with existing teaching models used in PMBIA, BICP, and GSMBC, while adding deliberate attention to psychological and social risk at every stage.

Step 1 — Assess

Establish the rider’s technical baseline, emotional state, and readiness for challenge. Observe first, with minimal coaching input, so you can set and refine coaching and lesson goals, and identify which domains may be key for individual and group progression.

- Use warm-ups to observe natural movement and foundational skills

- Identify strengths, gaps, and timing issues relevant to the session goals

- Check emotional readiness using a fear/comfort continuum and note confidence signals

- Assess for fatigue, focus, and overall cognitive load

- Confirm rider intent: goals, concerns, preferences, and any non-negotiables

This creates a clear starting point to understand what the riders can do comfortably and naturally, initial areas for improvement, and which risk domains to consider during the lesson.

Step 2 — Build the Learning Container

Before increasing technical or environmental challenge, instructors must establish the learning container—the lesson structure, clarity of objectives, and psychological safety riders need to engage with productive risk.

- Communicate session goals, terrain boundaries, skill objectives, lesson flow, and clear success criteria

- Explain how progression can and will unfold so riders understand what to expect and prepare for

- Clarify group flow, spacing, and pace to reduce uncertainty and comparison pressure

- Reinforce that challenge is individual, adjustable and rider-driven, including the option to pause or opt out

- Model professional presence that is calm, confident, and consistent

A well-built container reduces psychological and social risk before technical challenge increases.

Step 3 — Isolate

To drive successful drills and lessons instructors need to provide low-variable conditions so riders can learn core skills and mechanics without unnecessary emotional or environmental load. Isolation and focus on one variable allows instructors to deliberately reduce environmental and psychological risk while focusing attention on specific technical execution.

- Begin in low-consequence environments like parking areas and open fields

- Deliver skills-based instruction using clear, consistent language and guidance with minimal competing cues

- Demonstrate skills at rider-appropriate speed and scale

- Provide multiple demos, directing attention to focus students

- Provide one clear focus at a time

- Use repetition to build proprioception and early confidence

Isolation and specific focus create stability in practice. Progress only when outcomes are predictable and repeatable.

Step 4 — Consolidate

Transforming early success into reliable, repeatable performance is a primary goal of skills based teaching. Consolidation represents both stabilized skill execution and emotional response and should be verified before additional challenge is introduced.

- Use repetition to refine timing, motor patterns, and consistency

- Reinforce specific successes tied to mechanics or tactical decisions

- Identify and correct unhelpful patterns such as tension, fixation, or hurried execution

- Introduce visualization or mental rehearsal where appropriate as a tool for self-direction

- Monitor emotional state to ensure confidence remains stable as repetition continues

Consolidation bridges controlled learning and adaptable performance. It ensures riders can reproduce skills and outcomes reliably before risk increases through speed, complexity, or terrain.

Step 5 — Expand Through One Variable

Once skills are stable, introduce additional challenge by adjusting a single variable while keeping others consistent. This step is where risk is intentionally increased, and where progression decisions must be made deliberately.

- Select one variable to introduce manageable challenge, such as speed, timing, complexity, scale, or incremental terrain

- Maintain clarity about why the change is valuable and what success looks like

- Adjust challenge progressively rather than in large steps

- Repeat drills and challenges to consolidate new adaptations

- Observe emotional cues and confidence as challenge increases

- Provide supportive feedback to reinforce adaptation and learning

- Pause, reframe, or regress if signs of overload or shutdown appear

Progression at this stage should support riders becoming Comfortable, Consistent, and Correct (CCC) under increased demand before additional variables are introduced.

Step 6 — Application & Validation

Ultimately riders want to apply skills in real terrain under natural conditions. This is where environmental and psychological risk increase even if the skill itself has not changed. This step is about validating preparation, managing suitable conditions to build rider agency, and adapting instruction in response to how riders manage emotion and commitment in response to risk and consequence.

- Select incremental terrain or obstacles appropriate to rider readiness and lesson intent

- Use sessioning to introduce feature and trail complexity, and refine execution before increasing difficulty

- Set clear visualizations and focus cues before attempts

- Suggest one focus at a time, or a progressive execution strategy

- Continuously monitor emotional state and confidence, and provide psychological support as needed

- Adapt expectations, terrain choice, or task focus in response to hesitation, over-commitment, or breakdown

- Provide feedback tied directly to terrain outcomes and decision-making

Application does not require continuous trail or risk progression. Remaining on the same terrain to stabilize execution, consolidate skills and build confidence is often the correct outcome before moving on to harder things.

Step 7 — Review & Reflect

Reflection transforms lessons and experience into durable learning by helping riders interpret outcomes, calibrate confidence, and refine decision-making ideas and skills. This step develops metacognition—the ability to review progress, accurately self-assess readiness and manage risk independently.

- Encourage riders to self-assess outcomes and link successes or difficulties to specific skills, drills, decisions, or conditions

- Add coaching insights to reinforce accurate interpretation and provide validation and reframe negative feelings

- Normalize that recognizing limits and choosing not to take risks is skilled decision-making

- Revisit and recalibrate fear or comfort ratings from the start of the session and discuss what changed

- Capture clear takeaways for future practice, terrain choice, and progression

Effective reflection strengthens confidence grounded in experience and supports safer, more thoughtful riding and risk managment beyond the lesson environment.

Coaching Behaviours That Enable Positive Risk

Coaching behaviours form the instructional foundation of great lessons, with effective risk management and the application of positive risk shaping how riders experience challenge. Effective behaviors are covered in various curricula and highlights below specifically apply to the application of positive risk with students.

A. Communicate with Precision

- Use concise, unambiguous language

- Maintain consistent terminology

- Set expectations before introducing new challenge

- Focus gudiance on one idea or change at a time

B. Demonstrate with Intention

- Show skills at rider-appropriate scale and speed

- Use imperfect demonstrations when helpful to normalize error and learning

- Repeat demonstrations and validate understanding with riders

- Highlight timing and sequencing, not just outcomes

- Use leading questions with students to validate effectiveness

C. Select Terrain Strategically

- Know available options and pre-ride to prepare for lessons

- Align terrain with lesson goals and rider readiness

- Prioritize predictability and margin for error

- Progress terrain gradually rather than in large jumps

D. Protect Rider Autonomy

- Offer choices rather than mandatory prescriptions

- Encourage riders to select their own speed, line, and timing

- Reinforce that choosing alternate lines or opting out is skilled decision-making

E. Maintain Professional Presence

- Be professional, calm, encouraging, and attentive

- Avoid hype or emotional contagion

- Demonstrate patience and consistency

- Prioritize rider needs over terrain ambition

These behaviours reduce unnecessary risk and support learning across all domains.

Outcomes: What This Produces Over Time

When positive risk is applied intentionally, riders develop competencies across multiple domains beyond skills acquisition. This helps to develop agancy, self awareness and genuine confidence.

A. Technical

- Stronger timing, control, and body movement

- Improved consistency across varied terrain

- Greater ability to blend skills under pressure

B. Psychological

- More accurate self-assessment of readiness

- Stable performance in challenging environments

- Increased confidence and emotional resilience

C. Decision-making

- Better trail awareness, scanning skills, line choice and terrain assessment

- Improved anticipation and preparation for riding and maneuvers

- More reliable risk–reward evaluation

D. Behavioural

- Greater autonomy and agency

- Increased intrinsic motivation

- Thoughtful, safer riding habits

- Reduced susceptibility to social pressure

E. Developmental

- Faster, more stable skill acquisition

- Deeper engagement with the sport

- Emergence of independent, self-directed riders

Summary: What Positive Risk Actually Does

Risk is inherent in mountain biking. The goal of instruction is not to eliminate it, but to shape it into an intentional and productive tool for learning.

The Positive Risk framework operationalizes what many experienced instructors already do intuitively: reading riders, sensing thresholds, modulating challenge, and building learning containers that make productive risk-taking possible. It is intended as a complement to existing curricula—an additional lens that any trained instructor can apply to enhance lesson design, improve rider outcomes, and support consistent progression over time.

Positive Risk coaching produces riders who are technically competent, emotionally grounded, and capable of making safe, independent decisions—with or without a coach present.

[End]